VANK announced that it has launched a campaign to correct overseas textbooks after finding that widely used world history and geography textbooks repeatedly present Africa through a Eurocentric lens or reduce the continent to a collection of political and social problems.

VANK said it analyzed seven world history and geography textbooks that are commonly used in classrooms abroad and found that biased narratives about Africa were not isolated errors but structural patterns. Because many of these books are effectively treated as “standard texts” in high school curricula, international schools, and college entrance preparation programs in the United States and other countries, VANK warned that such portrayals can directly shape how learners around the world perceive Africa.

The study follows VANK’s earlier efforts to address distortions about Africa in Korean textbooks and biased entries in foreign dictionaries and digital encyclopedias. It is significant, the group said, because it is the first systematic review of overseas textbooks that are actually used in global education settings. The materials examined included world history and geography textbooks from major U.S. publishers such as Pearson and McGraw Hill, as well as test-preparation series for the AP World History exam.

Africa excluded as a historical actor

According to VANK, many world history textbooks describe Africa not as a place that actively shaped its own history, but as a passive continent changed mainly by outside forces.

In Pearson’s World Cultures: A Global Mosaic, a section on the African slave trade opens with the question, “Why did Europeans become interested in Africa?” placing Europe at the starting point of the story. VANK argued that this approach encourages students to understand world history through Western concerns rather than African historical contexts. The textbook also explains European enslavement of Africans by noting that Europeans believed Africans were better able to withstand the climate, a claim that reflects colonial justifications, while offering little explicit criticism of such views.

McGraw Hill’s Exploring Our World: People, Places, and Cultures similarly presents slavery as a response to Europe’s labor shortages and treats the slave trade largely as an economic activity. In doing so, the coercion, violence, and human rights abuses suffered by enslaved Africans are downplayed, while the abolition of slavery is described mainly as a decision made by European states. Africa is again pushed out of the role of historical agent. A similar pattern appears in sections on imperialism and colonial partition, where the textbooks focus on European economic and political goals while treating violence, coercion, and local resistance as secondary issues. As a result, Europe remains at the center of historical change, and African societies are pushed to the margins.

VANK found the same tendency in Barron’s AP World History: Modern PREMIUM. Rather than presenting Africa as a region that generated its own political and economic changes, the book repeatedly frames Africa as a place transformed only after European expansion and intervention. While European strategies and shifts in the global order are described in detail, African responses receive limited attention. VANK warned that this narrative structure risks portraying colonial rule as historically inevitable.

Violence softened through language

VANK also pointed to biased word choices that soften the reality of violence. Terms such as “change,” “effect,” “expansion,” “encounter,” and “development” are often used to describe invasions, forced labor, mass killings, and racial discrimination, making these events appear less brutal. By focusing on outcomes rather than processes, such language can blur responsibility and obscure harm.

In Pearson’s The Heritage of World Civilizations (combined volume, 7th edition), the slave trade is described as having had a “devastating impact” on African societies, yet the same sections repeatedly say that trade-based exchanges “enriched” the cultures and religions of the Americas. VANK said this framing shifts attention away from concrete suffering and toward notions of progress.

McGraw Hill’s Exploring Our World uses a chapter title asking, “How can we help Africa?” reinforcing a narrative that consistently places Africa as an object of aid. Poverty and social problems are highlighted, while African-led responses and internal change receive far less attention.

In Barron’s AP World History: Modern PREMIUM, African societies are frequently described using terms such as “tribal,” “traditional,” and “local,” with limited effort to connect them to modern political systems or complex social structures. Expressions like “primitive,” “backward,” and “underdeveloped” appear repeatedly, fixing Africa as a place that lags behind Western standards. In discussions of conflict, phrases such as “tribal conflict” or “tribal hatred” are used, raising concerns that events like the Rwandan genocide may be reduced to simple ethnic clashes, while the role of colonial powers in institutionalizing ethnic divisions is insufficiently explained.

A generalized and simplified Africa

VANK said that a lack of detailed information has led to widespread generalization and oversimplification. Across many textbooks, Africa is treated as a single, uniform society, with repeated statements beginning with “Africa is…” regardless of region, period, or political system. While Western industrialization, wars, and political history are covered in long and layered narratives, African social structures, ideas, independence movements, and internal politics are often handled briefly. VANK stressed that this imbalance reflects not just a difference in volume but a value judgment about what is considered “important history.”

In Pearson’s World Explorer: People, Places, and Cultures, postcolonial political instability in Africa is explained with little attention to Cold War intervention, artificial borders, or economic dependency. Instead, instability is broadly attributed to Africa’s own “immaturity.” South Africa’s apartheid system is described mainly in terms of laws and institutions, while state violence, forced removals, and repression are minimized.

McGraw Hill’s Exploring Our World explains African independence largely by stating that weakened European powers lacked the resources to prevent it, pushing African armed struggle and political organization out of view. This framing risks portraying independence as a passive result of external change rather than an outcome actively fought for by Africans.

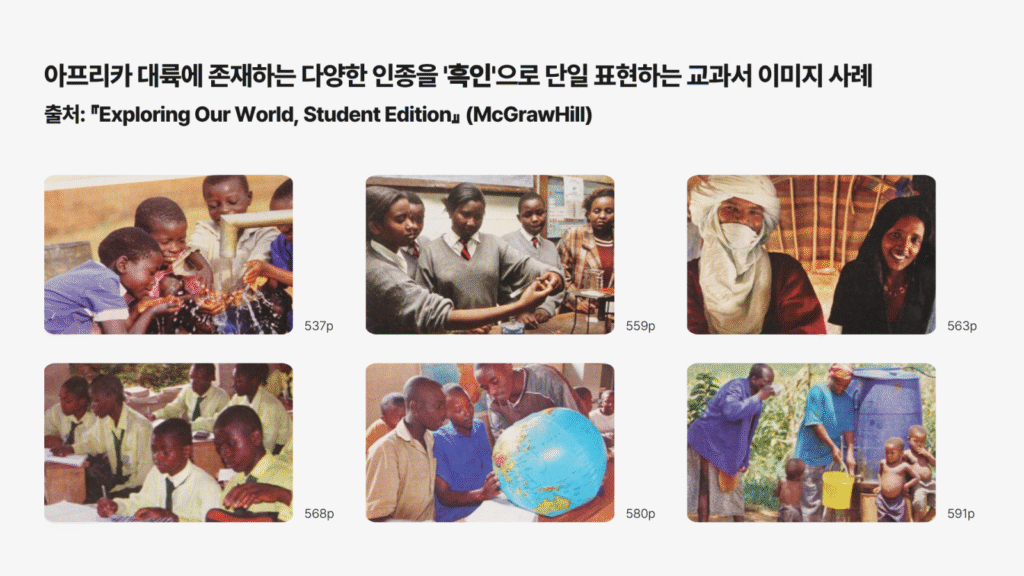

Distortions in images and maps

VANK said these biases are also visible in images and visual materials. In McGraw Hill’s Exploring Our World, photographs related to Africa largely feature Black individuals and emphasize poverty, disease, conflict, and traditional lifestyles. Such choices, VANK argued, encourage students to see Africa as racially and culturally uniform, failing to reflect the continent’s diversity of peoples, languages, and cultures.

In geography textbooks, images and questions highlighting “problem situations” are concentrated in Africa-related sections, reinforcing the idea that Africa is a place that always requires explanation or intervention.

VANK also noted the repeated use of the Mercator projection in world maps, including in Penguin’s The Penguin State of the World Atlas and Barron’s AP World History: Modern PREMIUM and How to Prepare for the SAT 2 World History. This projection significantly reduces Africa’s apparent size. While useful for navigation, VANK has long argued that its use in education distorts learners’ spatial understanding. The group found that many textbooks repeatedly included maps that visually shrink Africa’s true scale.

Toward a more balanced view of world history

Based on its findings, VANK said that portrayals of Africa in overseas world history textbooks repeatedly combine the exclusion of African agency, narratives that justify colonial rule, biased language, limited historical information, and imbalanced use of text and images.

The initiative is drawing attention because Korean youth researchers directly analyzed foreign textbooks and raised concerns about their content. As citizens of a country with its own colonial past, VANK members said they see examining how a continent is represented in world history education as an international responsibility.

Kim Ye-rae, a youth researcher at VANK, said foreign textbooks are not just learning materials but form part of public discourse that shapes how countries and regions are understood. “World history and geography textbooks create the basic framework through which students see the world,” she said, adding that repeated distortions can solidify into collective prejudice.

Baek Si-eun, another youth researcher, said the analysis shows that Africa is structurally portrayed as passive in world history. “Africa is depicted less as a historical subject that makes choices and resists, and more as a space that is acted upon,” she said, noting that violence linked to slavery and colonialism is softened through neutral language while African agency is pushed out of sight.

Lee Sei-yeon, also a youth researcher, argued that historical events emerge from complex political, social, and cultural contexts, making it essential to reflect African perspectives alongside external influences. She added that Korea’s own historical experience underscores the importance of fairness and balance in historical narratives.

Park Gi-tae, head of VANK, said the group’s move from correcting distortions about Korean history to examining Africa reflects an expanded sense of global civic responsibility. “We will continue to challenge narratives that portray certain regions only as problems or objects of aid,” he said, stressing that the goal is to reshape underlying perceptions in international education, not just to correct individual errors.

Previously, VANK led a campaign addressing biased portrayals of Africa in Korean textbooks. As a result, the Ministry of Education of Korea revised eight elementary social studies textbooks to reduce an exclusive focus on poverty and hunger and to include population size, technological development, and examples of exchange with Korea. VANK said this experience shows that public scrutiny can lead to real change.

Building on that effort, VANK plans to formally share its findings on overseas textbooks with publishers and educational institutions and to request specific revisions. Through cooperation with international civic groups and organizations, the group aims to continue addressing structural bias in global education and to promote a more balanced approach to teaching world history.